LSTM Neural Networks are interesting. There’s plenty of literature on the web about them, so I thought I’d cut to the chase and show how to implement a toy game.

In this game, we want to have a mouse and a cat in a room. The cat tries to eat the mouse, and the mouse tries to avoid being eaten.

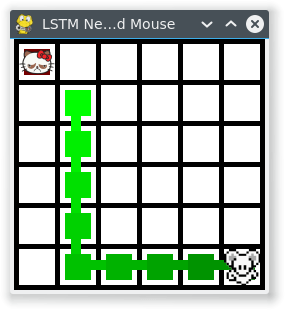

Cat & Mouse start randomly. Mouse is taught to run away from the stationary cat.

We will give the mouse and cat both an LSTM Neural Network brain, and let them fight it out.

This game will be implemented with a straight forward LSTM neural network. This means that it is supervised which means that our mouse and cat brains can only learn by example.

This is really important – it means that we can’t just have our mouse and cat learn for themselves. We could do that if we used genetic algorithms to develop the neural networks, but that’s not how we’re doing it here.

With all that said, let’s just dive straight in!

First, lets set up a sigmoid function and its derivative:

#!/usr/bin/python

import copy, numpy as np

import math

np.random.seed(0)

# compute sigmoid nonlinearity

def sigmoid(x):

output = 1/(1+np.exp(-x))

return output

# convert output of sigmoid function to its derivative

def sigmoid_output_to_derivative(output):

return output*(1-output)

class LSTM_Brain:

def __init__(self):

self.alpha = 0.1 # Training rate

self.input_dim = 4 # Number of parameters for the input. We input the position of the cat and the mouse.

self.hidden_dim = 16 # Size of a brain, so to speak. Feel free to vary

self.output_dim = 1 # Number of outputs. We output just the preferred direction, so just one.

self.brain_wipe()

def setupTraining(self):

self.input_values = list()

self.layer_2_deltas = list()

self.layer_1_values = list()

self.layer_1_values.append(np.zeros(self.hidden_dim))

self.total_abs_error = 0 # Store the error and smoothed error just for debugging information

def feedInputForGetOutput(self, inputData):

# inputData has only been tested for values between 0 and 1. Not sure how it works otherwise

assert len(inputData) == self.input_dim

X = np.array([inputData])

self.input_values.append(X)

# Feed the input to our 'brain', and return the output (e.g. which direction it thinks we should move in)

# hidden layer (input ~+ prev_hidden)

layer_1 = sigmoid(np.dot(X,self.synapse_0) + np.dot(self.layer_1_values[-1],self.synapse_h))

# output layer (new action)

self.layer_2 = sigmoid(np.dot(layer_1,self.synapse_1))

# store hidden layer so we can use it in the next timestep

self.layer_1_values.append(copy.deepcopy(layer_1))

return self.layer_2[0]

def teachError(self, error):

self.total_abs_error += sum(np.abs(error)) # We store this just for debugging

self.layer_2_error = np.array([error]).T

self.layer_2_deltas.append((self.layer_2_error)*sigmoid_output_to_derivative(self.layer_2))

def brain_wipe(self):

# initialize neural network weights. Forget everything we've learned

self.synapse_0 = 2*np.random.random((self.input_dim,self.hidden_dim)) - 1

self.synapse_1 = 2*np.random.random((self.hidden_dim,self.output_dim)) - 1

self.synapse_h = 2*np.random.random((self.hidden_dim,self.hidden_dim)) - 1

self.total_smoothed_abs_error = None

def learnFromGame(self):

future_layer_1_delta = np.zeros(self.hidden_dim)

synapse_0_update = np.zeros_like(self.synapse_0)

synapse_1_update = np.zeros_like(self.synapse_1)

synapse_h_update = np.zeros_like(self.synapse_h)

# Now, learn from the game

for time_tick in range(len(self.input_values)):

X = self.input_values[-time_tick-1]

layer_1 = self.layer_1_values[-time_tick-1]

prev_layer_1 = self.layer_1_values[-time_tick-2]

# error at output layer

layer_2_delta = self.layer_2_deltas[-time_tick-1]

# error at hidden layer

layer_1_delta = (future_layer_1_delta.dot(self.synapse_h.T) + layer_2_delta.dot(self.synapse_1.T)) * sigmoid_output_to_derivative(layer_1)

# let's update all our weights so we can try again

synapse_1_update += np.atleast_2d(layer_1).T.dot(layer_2_delta)

synapse_h_update += np.atleast_2d(prev_layer_1).T.dot(layer_1_delta)

synapse_0_update += X.T.dot(layer_1_delta)

future_layer_1_delta = layer_1_delta

self.synapse_0 += synapse_0_update * self.alpha

self.synapse_1 += synapse_1_update * self.alpha

self.synapse_h += synapse_h_update * self.alpha

if self.total_smoothed_abs_error is None:

self.total_smoothed_abs_error = self.total_abs_error

else:

self.total_smoothed_abs_error = self.total_smoothed_abs_error * 0.999 + 0.001* self.total_abs_error # Smooth it - for debugging only

At this point, we’ve got a basic LSTM.

Let’s now give it a world and put this brain in a mouse, and the mouse in a world.

class World:

# For directions, 0,0 is in the bottom left. Up is positive y. Direction is between 0 and 1

Up = 0.125

Right = 0.375

Down = 0.625

Left = 0.875

def __init__(self):

self.map_width = 6

self.map_height = 6

def resetWorld(self, cat_x, cat_y, mouse_x, mouse_y):

self.cat_x = cat_x

self.cat_y = cat_y

self.mouse_x = mouse_x

self.mouse_y = mouse_y

def distance_from_cat_x(self):

return self.mouse_x - self.cat_x

def distance_from_cat_y(self):

return self.mouse_y - self.cat_y

def moveMouse(self, time_tick, mouse_movement):

if mouse_movement < (self.Up + 0.125): # 0 to 0.25 is up. midpoint is 0.125

self.mouse_y += 1

elif mouse_movement < (self.Right + 0.125): # 0.25 to 0.5 is right. midpoint is 0.375

self.mouse_x += 1

elif mouse_movement < (self.Down + 0.125): # 0.5 to 0.75 is down. midpoint is 0.625

self.mouse_y -= 1

else:

self.mouse_x -= 1 # 0.75 to 1 is left. midpoint is 0.875

self.mouse_x = np.clip(self.mouse_x, 0, self.map_width-1)

self.mouse_y = np.clip(self.mouse_y, 0, self.map_height-1)

class GameWithStupidComputerTeacher:

def __init__(self):

self.debug = False # Whether to print out debug information

self.game_length = 10 # Number of moves a game should last for. We make this fixed, but we could make it variable

self.world = World() # The world to run in

def runGame(self, mouse_brain):

# Start a new game. We have a cat and a mouse

# at their starting position

self.world.resetWorld(np.random.randint(0,self.world.map_width),np.random.randint(0,self.world.map_height),

np.random.randint(0,self.world.map_width),np.random.randint(0,self.world.map_height))

mouse_brain.setupTraining()

for time_tick in range(self.game_length):

mouse_movement = mouse_brain.feedInputForGetOutput([(self.world.cat_x)/float(self.world.map_width-1),

(self.world.cat_y)/float(self.world.map_width-1),

(self.world.mouse_x)/float(self.world.map_height-1),

(self.world.mouse_y)/float(self.world.map_height-1)])[0]

ideal_direction = self.stupidTeacherForMouseGetIdealDirection()

mouse_brain.teachError([ideal_direction - mouse_movement])

# This is the direction the mouse brain says it wants to move in. We treat it as a clockwise compass reading

# Move the mouse accordingly

#self.world.moveMouse(time_tick, ideal_direction)

self.world.moveMouse(time_tick, mouse_movement)

# Game is completed. Learn from what we've been taught.

mouse_brain.learnFromGame()

def stupidTeacherForMouseGetIdealDirection(self):

# Play the role of a stupid teacher for the mouse, and direct the mouse to just run in the opposite direction from the cat

ideal_direction = 0

if self.world.distance_from_cat_x() >= 0:

# We could move right. But check if moving up or down makes more sense

if self.world.distance_from_cat_y() > self.world.distance_from_cat_x() and self.world.mouse_y != self.world.map_height - 1:

ideal_direction = self.world.Up

elif -self.world.distance_from_cat_y() > self.world.distance_from_cat_x() and self.world.mouse_y != 0:

ideal_direction = self.world.Down

elif self.world.distance_from_cat_y() > 0 and self.world.mouse_x == self.world.map_width - 1:

ideal_direction = self.world.Up

elif self.world.distance_from_cat_y() < 0 and self.world.mouse_x == self.world.map_width - 1:

ideal_direction = self.world.Down

else:

ideal_direction = self.world.Right

else:

if self.world.distance_from_cat_y() > -self.world.distance_from_cat_x() and self.world.mouse_y != self.world.map_height - 1:

ideal_direction = self.world.Up # up is the best way!

elif -self.world.distance_from_cat_y() > -self.world.distance_from_cat_x() and self.world.mouse_y != 0:

ideal_direction = self.world.Down # down is the best way!

elif self.world.distance_from_cat_y() >= 0 and self.world.mouse_x == 0:

ideal_direction = self.world.Up # can't go left, so go up!

elif self.world.distance_from_cat_y() < 0 and self.world.mouse_x == 0:

ideal_direction = self.world.Down # can't go left, so go down!

else:

ideal_direction = self.world.Left # left is the best way!

if self.debug:

print "cat:", self.world.cat_x, self.world.cat_y, "mouse:", self.world.mouse_x, self.world.mouse_y, "distance:", self.world.distance_from_cat_x(), self.world.distance_from_cat_y(), "ideal: ", ideal_direction

return ideal_direction

game = GameWithStupidComputerTeacher()

mouse_brain = LSTM_Brain()

print_csv = True

print_progress = not print_csv and True

if not print_csv:

graphics.init(game.world.map_width, game.world.map_height)

finish = False

for j in range(10000001):

game.debug = (j == 10000000) and not print_csv

game.runGame(mouse_brain)

if mouse_brain.total_smoothed_abs_error*4 < 1.2:

finish = True # An average of making 1 error per game

# print out progress

if (print_progress and j % 1000 == 0) or finish:

mouse_x = [int(x[0][2]*(game.world.map_width-1)) for x in mouse_brain.input_values]

mouse_y = [int(y[0][3]*(game.world.map_height-1)) for y in mouse_brain.input_values]

cat_x = [game.world.cat_x] * len(mouse_brain.input_values)

cat_y = [game.world.cat_y] * len(mouse_brain.input_values)

print "Game: ", j

print "cat x: ", cat_x

print "cat y: ", cat_y

print "mouse x:", mouse_x, " Errors:", '%.1f'%(mouse_brain.total_abs_error*4), "Smoothed Errors:", '%.1f'%(mouse_brain.total_smoothed_abs_error*4)

print "mouse y:", mouse_y

print

graphics.updateGraphics(cat_x, cat_y, mouse_x, mouse_y)

if print_csv and j % 1000 == 0:

print j, ",", mouse_brain.total_smoothed_abs_error*4

if finish:

break

At the end of this, we have a mouse that learns to run away from a stationary cat.

The teacher is teaching the mouse to:

1. Move away from the cat, in the direction that you are already furthest in.

2. Unless there you come to a wall. In which case move along the wall, away from the cat.

For a toy example, this is relatively challenging since the mouse neural net is being fed the absolute position of the mouse and the cat,

and so needs to learn to take the difference between the positions, judge which is largest, and modify the behaviour if near a wall.

It takes approximately 1 million games, with each game being 10 moves, for the mouse to learn to follow the teachers’ instruction with only 1.4 mistakes per game (averaged over 1000 games). Reducing this to 1 mistake per game took a further 2 million games and took 40 minutes CPU time on my laptop.

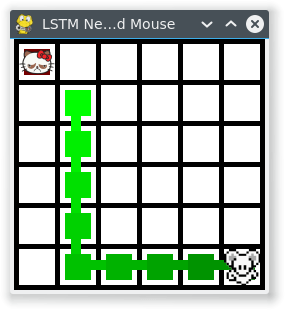

Here is an example game: (The GUI was done in pygame btw)

Cat & Mouse start randomly. Mouse is taught to run away from the stationary cat.

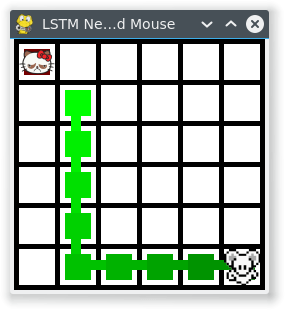

And here’s an example mistake that it made even after 2 million training games:

Example mistake, after 2 million training games. The mouse takes a step towards the cat.

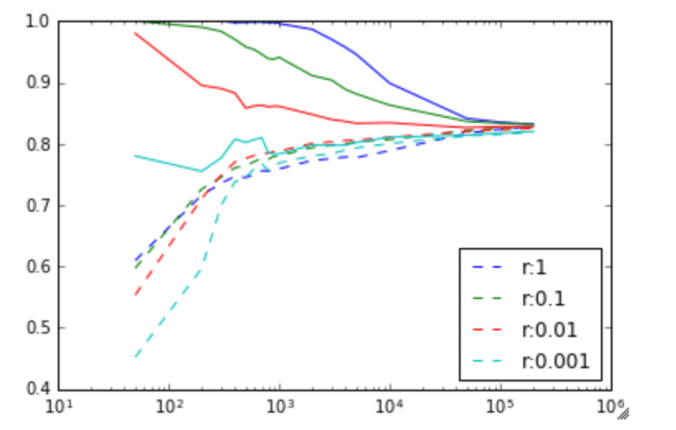

I played about with different training rate values (alpha in the code) but the learning rate didn’t seem dependent upon it.

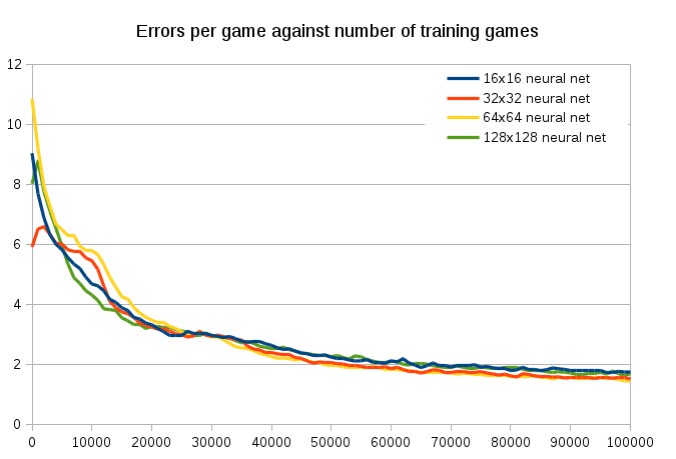

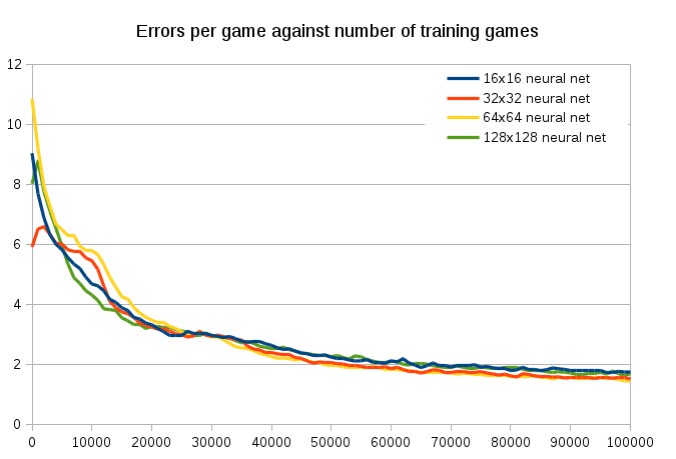

I tested increasing the hidden net from 16 to 32, and that made a pretty big difference. To reach an accuracy of 1.2 mistakes per game took:

- 16×16 hidden layer took 8m40s and 716342 games

- 32×32 hidden layer took 3m29s and 239721 games

- 64×64 hidden layer took 3m13s and 216513 games

- 128×128 hidden layer took 5m45s and 279732 games

Interestingly, if you compare the first 100,000 games the neural net size makes hardly no difference at all. They all get down to an error of about 2 at about the same rate. It’s also cool to see that the large 64×64 neural net takes about 30,000 training games to catch up with the small neural networks, since it has a much larger matrix to tame. Yet the 128×128 is much quicker to train. I don’t know why.

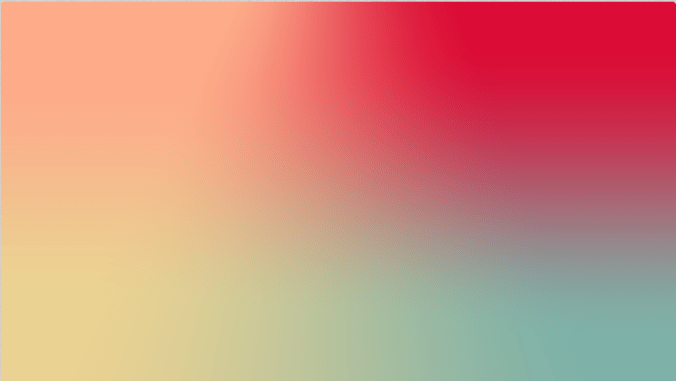

I also wrote a small program to display the synapses_0 matrix, which converts the input to the hidden matrix size, and plotted its against time. I also attempt to show how it is mapping the four inputs to the output by showing our four colours would be transformed by the matrix. While it is pretty to watch, it’s hard to see anything useful from it.

The synapses_0 matrix values, plotted in grayscale, and how it combines with the inputs. Each frame is 10,000 training games.

The initial and final state:

Initial random state

Final trained state, 800000 games

Graphics

For the sake of completeness, this is the graphics.py

import pygame

MAP_WIDTH = 10

MAP_HEIGHT = 10

# This sets the margin between each cell

MARGIN = 5

WINDOW_SIZE = [255, 255]

def lightened(color, amount):

h, s, l, a = color.hsla

if l+amount &gt; 100: l = 100

elif l+amount &lt; 0: l = 0

else: l += amount

color.hsla = (h, s, l, a)

return color

def init(map_width, map_height):

global WINDOW_SIZE, MAP_WIDTH, MAP_HEIGHT, screen, clock, cat_image, mouse_image, grid_width, grid_height

MAP_WIDTH = map_width

MAP_HEIGHT = map_height

grid_width = (WINDOW_SIZE[0] - MARGIN) / MAP_WIDTH - MARGIN

grid_height = (WINDOW_SIZE[1] - MARGIN) / MAP_HEIGHT - MARGIN

# Round the window size, so that we don't have fractions

WINDOW_SIZE = ((grid_width + MARGIN) * MAP_WIDTH + MARGIN, (grid_height + MARGIN) * MAP_HEIGHT + MARGIN)

# Initialize pygame

pygame.init()

# Set the HEIGHT and WIDTH of the screen

screen = pygame.display.set_mode(WINDOW_SIZE)

# Set title of screen

pygame.display.set_caption(&quot;LSTM Neural Net Cat and Mouse&quot;)

# Used to manage how fast the screen updates

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

cat_image = pygame.image.load(&quot;cat.png&quot;)

mouse_image = pygame.image.load(&quot;mouse.png&quot;)

mouse_image = pygame.transform.smoothscale(mouse_image, (grid_width, grid_height))

cat_image = pygame.transform.smoothscale(cat_image, (grid_width, grid_height))

def updateGraphics(cat_x, cat_y, mouse_x, mouse_y):

for event in pygame.event.get(): # User did something

if event.type == pygame.QUIT: # If user clicked close

done = True # Flag that we are done so we exit this loop

pygame.quit()

return False

# Set the screen background

screen.fill(pygame.Color(&quot;black&quot;))

# Draw the grid

for row in range(MAP_HEIGHT):

for column in range(MAP_WIDTH):

pygame.draw.rect(screen,

pygame.Color(&quot;white&quot;),

[(MARGIN + grid_width) * column + MARGIN,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * row + MARGIN,

grid_width,

grid_height])

for i in range(len(mouse_x)):

color = pygame.Color(&quot;green&quot;)

color = lightened(color, -30*i/len(mouse_x))

pygame.draw.rect(screen,

color,

[(MARGIN + grid_width) * mouse_x[i] + MARGIN*2,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - mouse_y[i] - 1) + MARGIN*2,

grid_width - MARGIN*2,

grid_height - MARGIN*2])

if i != len(mouse_x) - 1:

pygame.draw.lines(screen,

color,

False,

[((MARGIN + grid_width) * mouse_x[i] + (MARGIN + grid_width)/2,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - mouse_y[i] - 1) + (MARGIN + grid_height)/2),

((MARGIN + grid_width) * mouse_x[i+1] + (MARGIN + grid_width)/2,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - mouse_y[i+1] - 1) + (MARGIN + grid_height)/2)],

10)

for i in range(len(cat_x)):

color = pygame.Color(&quot;red&quot;)

color = lightened(color, -30*i/len(cat_x))

pygame.draw.rect(screen,

color,

[(MARGIN + grid_width) * cat_x[i] + MARGIN*2,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - cat_y[i] - 1) + MARGIN*2,

grid_width - MARGIN*2,

grid_height - MARGIN*2])

if i != len(cat_x) - 1:

pygame.draw.lines(screen,

color,

False,

[((MARGIN + grid_width) * cat_x[i] + (MARGIN + grid_width)/2,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - cat_y[i] - 1) + (MARGIN + grid_height)/2),

((MARGIN + grid_width) * cat_x[i+1] + (MARGIN + grid_width)/2,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - cat_y[i+1] - 1) + (MARGIN + grid_height)/2)],

10)

screen.blit(mouse_image, ((MARGIN + grid_width) * mouse_x[-1] + MARGIN,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - mouse_y[i-1] - 1) + MARGIN))

screen.blit(cat_image, ((MARGIN + grid_width) * cat_x[-1] + MARGIN,

(MARGIN + grid_height) * (MAP_HEIGHT - cat_y[i-1] - 1) + MARGIN))

# Go ahead and update the screen with what we've drawn.

pygame.display.flip()

# Limit to 60 frames per second

clock.tick(60)

return True